The Psychology of Procrastination and Anxiety: Models, Research, and Clinical Formulation

- 2 days ago

- 14 min read

Part 1: conceptual grounding and shame reduction

Part 2: starting strategies and behavioural entry points

Part 3: executive load, neurodivergence, and adaptations

CFT companion: threat regulation and self-criticism

Who this page is for

This article (Part 4) summarises the models that sit underneath the practical strategies used in Parts 1 to 3.

This is useful for trainees, practitioners, supervisors, educators, and psychologically informed readers who want to see the theory and formulation logic behind procrastination and anxiety.

It is designed to be scannable, and also rigorous enough to bookmark. You can read it in order, or use it as a reference.

If you are scanning, begin with the ‘Formulation map: dominant maintaining process’ map and go straight to the model. If you are formulating clinically, the ‘Clinical integration guide’ tends to be the most practical anchor.

What this article covers

Introduction and definitions

Procrastination as short-term mood regulation

Key clinical models: CBT reinforcement, perfectionism, social-evaluative threat, intolerance of uncertainty, CFT

Extended formulations: Self-discrepancy (ought-self) and vulnerability pathways

Clinical integration: formulation template and intervention matching

Jump to a section

Introduction | Why procrastination is not one thing | Procrastination as short-term mood regulation | CBT | Perfectionism | Social threat | Intolerance of Uncertainty (IU) | Self-discrepancy | Vulnerability | CFT | Neurodivergent | Cultural context | Clinical guide | Resources | References

Introduction

Procrastination and anxiety often overlap in practice, but the maintaining processes can differ. In many presentations, the loop is organised by three interacting threat processes: evaluation threat (fear of being judged), standards threat (fear of not being good enough), and uncertainty threat (fear of acting without certainty).

These are not categories of people, they are processes that can become dominant in a given task context. In real life, more than one process may be active; the clinical task is to identify the dominant maintaining process for this task, in this context.

Compassion Focused Therapy (Gilbert, 2014) conceptualises these as threat regulation processes, which is why regulation tends to come first, then behaviour change; it is often what makes behaviour change possible to implement.

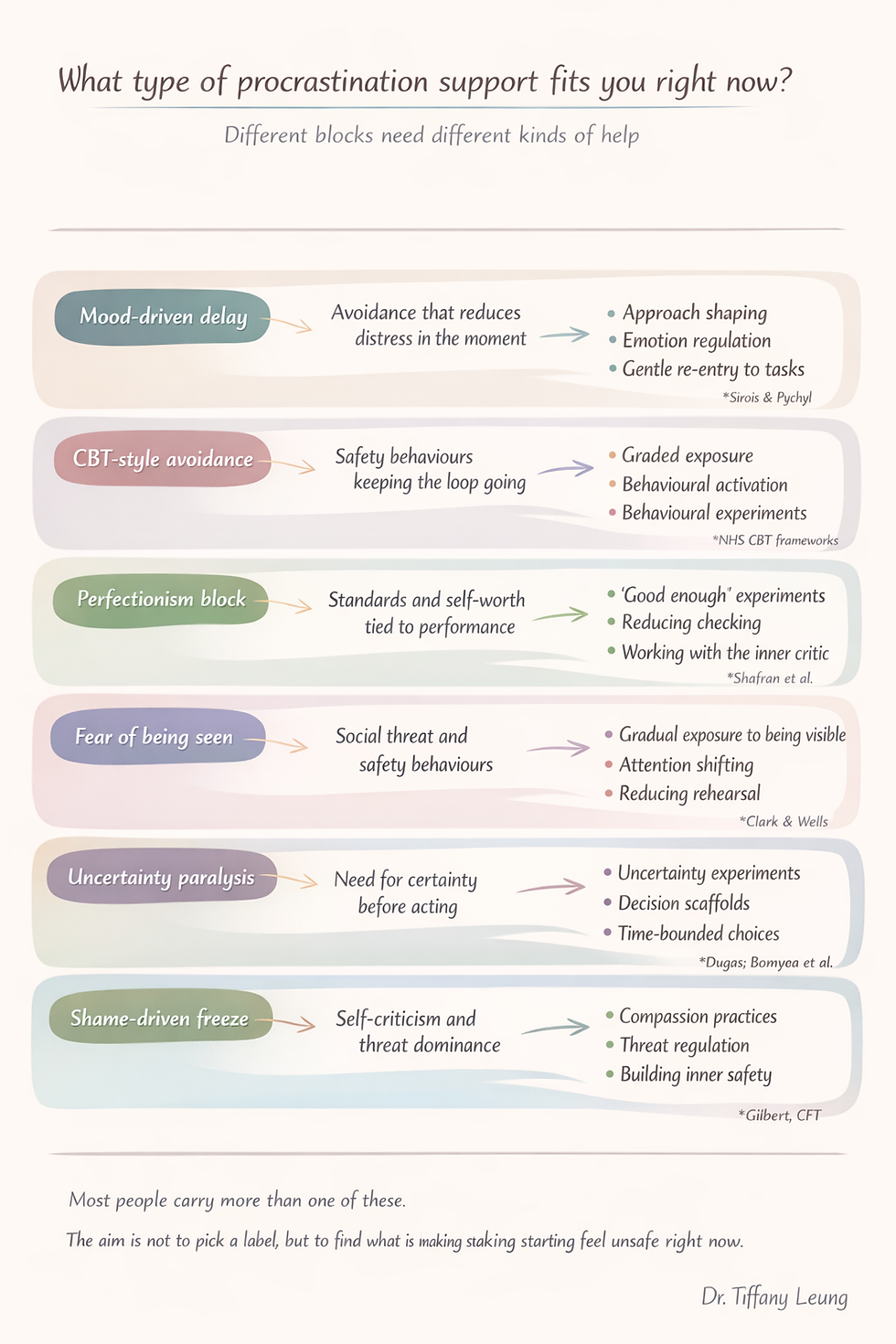

Formulation map: dominant maintaining process

If you want a quick route, start by identifying which process is dominant in the moment, then match it to a model:

Evaluation threat (fear of being judged) → Social evaluative threat formulation and safety behaviours (Clark and Wells, 1995)

Standards threat (fear of not being good enough) → Clinical perfectionism and self-criticism loops (Shafran, Cooper and Fairburn, 2002)

Uncertainty threat (fear of acting without certainty) → Intolerance of uncertainty model and uncertainty experiments (Dugas et al., 1998; Bomyea, Ramsawh and Ball, 2015)

Overload and initiation difficulty → Executive functioning and neurodivergent pathways under stress (Diamond, 2013; Barkley, 2012)

Shame and self-attack across all of the above → CFT as the integrative regulator of threat and action (Gilbert, 2014)

Many clients show a mixed presentation; use this as an initial formulation hypothesis, then test it against what maintains the loop in practice.

Why procrastination is not one thing

Procrastination is often discussed as if it is a single behaviour with a single cause. Clinically, it rarely is. Two people can show the same pattern on the outside, delay, miss deadlines, freeze before starting, but be driven by very different internal processes.

If we collapse these processes into one label, we risk offering the wrong kind of help, and unintentionally increasing shame.

A useful starting point is to separate three constructs that often get mixed together. This distinction changes formulation and intervention choice. (Steel, 2007)

Three constructs that get conflated

Procrastination is a voluntary delay of an intended task, despite expecting the delay to make things worse. The person usually understands the cost, and feels caught in a self-defeating loop. (Steel, 2007)

Avoidance or safety behaviour is an action designed to reduce emotional consequence. This threat might be shame, evaluation, uncertainty, or the fear of an emotional crash. Delay can function as a safety behaviour when the task feels like exposure. (Clark and Wells-informed approaches; see clinical summaries in later sections)

Executive functioning difficulty involves initiation, sequencing, working memory load, switching, and sustaining attention. From the outside it can look like procrastination, but inside it can feel like not being able to organise the first step, especially under stress, sensory load, or competing demands. This is particularly relevant for ADHD and autistic experiences, and also for burnout states.

If the primary driver is threat and shame, skills alone often fail, because the nervous system still reads the task as unsafe. If the primary driver is executive load, reassurance alone can fail, because the cognitive mechanics are still overloaded. Many people carry both patterns, so integration is often the real work.

Procrastination as short-term mood regulation

Even though people procrastinate for different reasons, there is one core mechanism that helps organise the pattern across presentations. Procrastination often works as a form of short-term mood regulation. It is a way of reducing immediate discomfort now, at the cost of increasing pressure later. (Sirois and Pychyl, 2013)

This tends to mean that procrastination can look irrational from the outside and still feel sensible from the inside. The behaviour is not chosen because it is helpful long-term, it is chosen because it offers relief in the moment.

Clinically, I use this account when delay reliably reduces immediate distress, even if the longer-term costs are clear and repeated.

Relief now, cost later

A typical procrastination loop looks like this:

A task appears.

It triggers an internal state, anxiety, self-doubt, shame, uncertainty, or overload.

The person delays, which brings short relief.

Relief reinforces the delay.

Later, time pressure, self-criticism, and consequences increase, which raises threat further. The next attempt to start carries even more emotional weight. (Sirois and Pychyl, 2013)

This model highlights a predictable learning cycle. If delay reliably reduces distress, the nervous system will keep returning to it.

Why this is not simply low motivation

Motivation language can be misleading. Many people who procrastinate care deeply. What fails is not desire, but the capacity to stay with discomfort long enough to begin, especially when the task is tied to evaluation, identity, or relational meaning. When we misname this as laziness, we strengthen shame, and shame increases what is at stake, which strengthens avoidance. (Sirois and Pychyl, 2013)

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT)

(functional analysis and reinforcement)

CBT contributes something very practical here: a mechanism map that explains how procrastination is maintained.

In CBT terms, the key process is negative reinforcement. A behaviour that reduces distress quickly is more likely to be repeated, even if it creates long-term harm.

NHS self-help guidance often draws on CBT principles for approaching tasks and reducing avoidance patterns. (NHS, n.d.)

CBT invites us to track the interaction between thoughts, feelings, body sensations, behaviours, and consequences.

For procrastination, the behaviour is often delay, distraction, over-preparing, or avoidance. The short-term consequence is relief.

The long-term consequence is increased pressure, loss of confidence, and a stronger association between the task and sense of consequence.

In formulation terms, the question becomes: what exactly is being regulated by the avoidance? Anxiety, shame, uncertainty, sensory overload, fear of being judged, fear of inadequacy. Different answers lead to different targets.

Avoidance as safety behaviour that trains the system

Safety behaviours are actions that reduce perceived emotional threat. They feel protective, and often are protective, but they also teach the nervous system that the situation is dangerous.

Avoidance prevents new learning. It blocks the corrective experience of “I can begin, be imperfect, be seen, and still be safe.”

That is why pushing harder often fails. The system is not refusing work, it is refusing what is at stake.

What CBT is excellent for in procrastination work

Graded exposure to avoided tasks, especially when fear of being judged is present

Behavioural activation, planning, and action scaffolding

Behavioural experiments targeting rigid standards and “good enough” beliefs

Relapse prevention framed without moral judgement (NHS, n.d.)

Most real procrastination cycles involve more than one process, which is why mapping the dominant driver matters.

Identify what maintains the loop, then match the intervention to that mechanism.

Perfectionism and standards threat

(fear of not being good enough)

When procrastination is powered by standards threat, the task is not only a task. It becomes a verdict on the self. The question underneath is often, “If I do not do this perfectly, what will it mean about me?”

Clinical perfectionism, the maintenance cycle

A widely used cognitive behavioural account describes clinical perfectionism as a pattern where self-evaluation becomes overly dependent on meeting demanding standards, despite significant costs. (Shafran, Cooper and Fairburn, 2002)

The maintenance cycle often looks like this:

Why perfectionism fuels procrastination

Perfectionism fuels delay through predictable mechanisms:

A first draft feels like exposure rather than progress

All-or-nothing thinking makes “starting small” feel pointless

Self-criticism raises perceived threat before the task even begins

Over-preparing becomes a way to control uncertainty

Avoidance protects the self from shame, at least temporarily (Shafran, Cooper and Fairburn, 2002)

Perfectionism is consistently associated with distress and impairment, but pathways vary. For some, it is mainly self-criticism; for others it is fear of being judged; for others it is rigid standards linked to identity and belonging. The aim is not to label perfectionism as pathology, but to identify when standards have become a threat system, not a values system. (Shafran, Cooper and Fairburn, 2002)

Cultural resonance, without stereotyping

In some families, communities, and professional cultures, achievement can carry relational meaning, duty, face, belonging, and safety. This can intensify standards threat without reducing it to personality.

Some university counselling resources in Hong Kong, for example, frame procrastination within pressure, self-expectations, and emotional wellbeing in a culturally adaptive way. (The Chinese University of Hong Kong, n.d.; Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, n.d.)

Notice how standards threat and evaluation threat often travel together, but they do not require the same intervention target.

Social-evaluative threat

(fear of being judged)

In social-evaluative threat, the feared consequence is not only failure. It is being seen failing, being exposed as inadequate, disappointing someone, or losing face. Many modern tasks are socially loaded even when completed alone. Emails, applications, reports, presentations, and submissions all carry an imagined audience.

The invisible audience is the internal experience of being watched, assessed, or measured, even when nobody is present. The body responds as if evaluation is happening now. This can make pressing send feel like stepping onto a stage.

Delay becomes a safety behaviour. If you do not submit, you cannot be judged. If you keep rewriting, you postpone exposure.

Example Formulation

A common formulation pattern is:

Perceived social danger increases self-focused attention and monitoring, which increases anxiety and image management, which increases safety behaviours such as over-rehearsing, avoiding, delaying, and perfecting.

The short-term result is relief.

The long-term result is the maintenance of perceived threat, because the person never learns that being seen can be survivable. (Clark and Wells, 1995)

When it looks like procrastination, but is actually social threat “I cannot press send,” even when the content is ready “I keep rewriting,” because I imagine judgement “I do everything except submission,” because the final step feels like exposure

Intolerance of uncertainty (IU)

Some people procrastinate not because they fear being judged or being inadequate, but because uncertainty itself feels unbearable. The nervous system treats ambiguity as danger.

IU in lived experience language

You might recognise IU in thoughts like: “I cannot begin until I know it will be the right version.” “I need more information before I can act.” “I do not want to start and discover I have chosen the wrong approach.”

This is most likely when action is delayed until uncertainty feels lower.

Delay becomes an attempt to eliminate uncertainty before acting.

Clinical implications

A classic conceptual model of worry describes intolerance of uncertainty as a key feature, alongside beliefs about worry, negative problem orientation, cognitive avoidance, and maladaptive coping strategies. (Dugas et al., 1998)

IU-driven procrastination often involves over-researching, decision paralysis, and repeated checking. The intervention target is rarely “confidence.” It is the capacity to act without certainty, through behavioural experiments, decision scaffolding, and graded exposure to ambiguity.

There is evidence that intolerance of uncertainty can reduce through CBT-based approaches, and reductions in IU may be related to reductions in worry in some samples. It is best held as a process variable rather than a single explanatory key. (Bomyea, Ramsawh and Ball, 2015)

By this point, the models are less about motivation, and more about what the system is trying to protect you from.

Self-discrepancy, the ought-self and inherited standards

Self-discrepancy theory (Higgins, 1987) highlights the distress that arises when the actual self feels far from internalised ideals or obligations, especially the ought-self. In real life, the ought-self often carries voices from family, culture, institutions, and professional hierarchies.

This matters because standards threat is not always self-generated. It can be inherited. When a task activates the ought-self, procrastination can function as protection from shame, duty failure, and relational consequence.

This lens often strengthens cultural formulation because it makes space for the question: whose standard is this, and what is at stake if it is not met?

I reach for this model when the distress feels moral or relational, as though not meeting the standard would mean failing a duty, disappointing someone, or losing belonging, not simply falling short on a task.

Vulnerability pathways, why some systems become threat-sensitive

A vulnerability framework offers a dignified way to explain why some nervous systems become more threat-sensitive. Broadly, vulnerability can arise from temperament, experiences that teach the world is hard to control, and learning histories that pair mistakes with consequence (Barlow, 2002).

This supports the stance that many procrastination patterns are not chosen. They are learned adaptations shaped by what the system has lived through.

Compassion Focused Therapy (CFT) as an integrative lens

(shame, self-criticism, threat regulation)

CFT (Gilbert, 2014) is often the missing piece when procrastination work becomes stuck. Not because compassion is a replacement for action, but because compassion shifts the nervous system state required for action.

Compassion is regulation, not indulgence

Compassion, in CFT, is a motivation and capacity to respond to suffering with care, courage, and wisdom.

When self-criticism is high, the threat system is activated. A threatened system is more likely to avoid. Compassion reduces threat, increases affiliative safety, and makes approach behaviour more possible. (Gilbert, 2014)

This is often why people can understand tools cognitively and still feel unable to begin. Skills are less accessible when threat is dominant.

CFT describes three interacting systems: threat (protection and alarm), drive (achievement and pursuit), and soothing or affiliative safety (rest, connection, settling). Procrastination often appears when perceived risk dominates, drive becomes conflicted, and soothing is under-accessed. Supporting soothing is not about removing responsibility, it is about enabling the system state needed for sustainable effort. (Gilbert, 2014)

CFT is often a fitting explanation when shame, harsh self-criticism, relational trauma histories, or culturally internalised performance-worth beliefs are prominent. It helps people build a different internal relationship with effort, so that behaviour change is not powered by self-attack.

For the full CFT map and practical nervous system applications, see my companion article: Struggling to Relax? A Compassionate Guide Using Compassion Focused Therapy.

Neurodivergent pathways

Some procrastination presentations are best understood as executive load under stress, not resistance.

Clinically, executive load can be trait-based (neurodevelopmental) or state-based (burnout, depression, sleep deprivation), so context and history matter.

Executive load and threat amplification

Initiation and switching rely on working memory, sequencing, prioritising, and state transitions (Diamond, 2013).

For ADHD and autistic experiences, and for sensory processing differences, those transitions can be genuinely taxing, especially under stress (Barkley, 2012).

Stress adds internal noise, narrows attention, and reduces cognitive flexibility, which makes starting harder.

A second layer is history. When someone has lived with chronic correction, misunderstanding, or masking, shame and evaluation threat can sit on top of executive load, amplifying the block.

Do not mis-formulate executive load as resistance

When executive load is misread as laziness or defiance, shame increases and engagement drops. Clinically, we aim to match the intervention to the mechanism: reduce friction, externalise steps, scaffold transitions, and address relational shame where it exists. This is not indulgence. It is accurate formulation.

For neurodivergent-specific guidance and adaptations, see Part 3 and the ADHD therapy series.

Cultural and relational context

Culture is not a theme you add at the end. It shapes what the task means. It shapes what failure would cost. It shapes what being seen might imply.

This is less about the task and time-management itself, and more about relational, face, duty, hierarchy, belonging.

When fear is relationally based: belonging, face, duty, hierarchy

For some readers, the threat is not only personal. It is relational. A task can become an exposure to losing face, disappointing family, violating duty, or being judged within a hierarchy.

Migration, professional class mobility, and minority stress can also intensify the “prove yourself” context.

When this is present, procrastination is often protection from relational consequence, not avoidance of effort.

How to better understand cultural and relational context

Rather than assuming meaning, we listen for it. Useful questions include:

What would it mean about you if this went wrong?

Who feels present when you imagine completing it?

Whose standards are you carrying here?

What does “mistakes” mean in your family, school, or workplace culture?

What consequence feels most risky, practical, relational, or internal?

The aim is not cultural explanation, it is identifying what the task symbolises in that person’s relational world.

If the client says “I just cannot start,” ask: is this fear of evaluation, fear of inadequacy, fear of uncertainty, executive overload, or a mixed pattern under stress?

Clinical integration guide

“so what do I do with this?”

What I hope to share about this article, is not to tell you to pick one model and force everything into it. The aim is to identify the dominant maintaining processes, then match intervention targets with precision.

Consider recommending therapy when procrastination is persistent and shame-based, functioning is significantly impacted, avoidance is trauma-linked or relationally loaded, or neurodivergent burnout and executive overload are prominent. Therapy offers formulation, shame repair, and a sustainable plan, not a new set of demands.

Recommended resources

For clients

NHS Every Mind Matters resources (NHS, n.d.) can be a gentle starting point for CBT-informed self-help.

The Centre for Clinical Interventions procrastination modules (2025) offer structured worksheets and practical techniques.

For practitioners

Steel (2007) offers a strong definitional and correlational foundation for procrastination research.

Sirois and Pychyl (2013) provides the mood regulation account that unifies many clinical presentations.

Shafran, Cooper and Fairburn (2002) provides a clear CBT model of clinical perfectionism.

Dugas et al. (1998) provides a conceptual model for intolerance of uncertainty and worry processes.

Gilbert (2014) provides the theoretical foundation for CFT as threat regulation and shame work.

Continue the series

If you want the applied version of these models, return to Parts 1 to 3 for strategies and adaptations.

Part 1: Why procrastination is not laziness

Part 2: Why pressure makes starting harder

Part 3: When starting is hard (neurodivergent pathways)

Part 4: The psychology behind the series (models, evidence, and clinical integration) (This page) If you are a clinician or trainee, you may want to bookmark this page as the models hub for the series.

References

Barkley, R.A. (2012) Executive Functions: What They Are, How They Work, and Why They Evolved. New York: Guilford Press.

Barlow, D.H. (2002) Anxiety and Its Disorders: The Nature and Treatment of Anxiety and Panic (2nd edn). New York: Guilford Press.

Bomyea, J., Ramsawh, H. and Ball, T.M. (2015) Intolerance of uncertainty as a mediator of reductions in worry in a cognitive behavioral treatment for generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. Available at: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4480197/

Centre for Clinical Interventions (2025) Procrastination: Self-help resources. Available at: https://www.cci.health.wa.gov.au/resources/looking-after-yourself/procrastination

Clark, D.M. and Wells, A. (1995) ‘A cognitive model of social phobia’, in Heimberg, R.G., Liebowitz, M.R., Hope, D.A. and Schneier, F.R. (eds.) Social Phobia: Diagnosis, Assessment, and Treatment. New York: Guilford Press, pp. 69–93.

Diamond, A. (2013) ‘Executive functions’, Annual Review of Psychology, 64, pp. 135–168.

Dugas, M.J., Gagnon, F., Ladouceur, R. and Freeston, M.H. (1998) Generalized anxiety disorder: a preliminary test of a conceptual model. Behaviour Research and Therapy. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9613027/

Gilbert, P. (2014) The origins and nature of compassion focused therapy. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. Available at: https://self-compassion.org/wp-content/uploads/publications/GilbertCFT.pdf

Higgins, E.T. (1987) ‘Self-discrepancy: A theory relating self and affect’, Psychological Review, 94(3), pp. 319–340.

Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, Counseling and Wellness Center (n.d.) No More Procrastination. Available at: https://counsel.hkust.edu.hk/uploads/publication/17/procrastination.pdf

NHS (n.d.) Tackling your to-do list. Every Mind Matters. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/every-mind-matters/mental-wellbeing-tips/self-help-cbt-techniques/tackling-your-to-do-list/

Shafran, R., Cooper, Z. and Fairburn, C.G. (2002) Clinical perfectionism: a cognitive-behavioural analysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12074372/

Sirois, F. and Pychyl, T. (2013) Procrastination and the priority of short-term mood regulation: Consequences for future self. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. Available at: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/id/eprint/91793/1/Compass%20Paper%20revision%20FINAL.pdf

Steel, P. (2007) The nature of procrastination: A meta-analytic and theoretical review of quintessential self-regulatory failure. Psychological Bulletin. Available at: https://studypedia.au.dk/fileadmin/www.studiemetro.au.dk/Procrastination_2.pdf

The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Wellness and Counselling Centre (n.d.) Say No to Procrastination. Available at: https://wacc.osa.cuhk.edu.hk/en/article/say-no-to-procrastination/

The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Wellness and Counselling Centre (n.d.) 踢走拖延. Available at: https://wacc.osa.cuhk.edu.hk/tc/article/say-no-to-procrastination/

Comments