When Starting Is Hard: Procrastination, the Nervous System, and Neurodivergent Reality

- Dr Tiffany Leung

- 2 days ago

- 11 min read

In Part 1, we explored procrastination as protection, not laziness.

In Part 2, we looked at how pressure and fear backfire.

Part 3 adds one more layer: sometimes the struggle is also about how your nervous system handles starting and overload.

On this page

Why your system resists starting

For many people, procrastination has never felt neutral.

It has been followed by years of being corrected, watched, and quietly compared.

You might have learned early that you were “too slow,” “too scattered,” “not trying hard enough,” or “wasting your potential.”

Over time, those messages can become internalised, even when you are actually working harder than most just to keep up.

When your nervous system processes information differently, everyday tasks can require more filtering, more organising, and more emotional regulation.

This is especially true when there is sensory input to manage, competing demands, or unclear instructions.

Add to that the effort of masking, appearing calm, focused, and competent when your system feels busy or overloaded, and fatigue builds long before a task even begins.

This is why many people who struggle with procrastination are not careless or unmotivated.

They are chronically overcorrecting.

They are constantly adjusting themselves to meet environments that were not designed for their way of thinking, sensing, or moving through the world.

The delay you see on the outside is often the after-effect of intense internal labour.

If you have lived with chronic misunderstanding, you may have learned to brace before you try.

You may double check everything, rehearse conversations, postpone sending work until it feels “safe enough,” or wait until the last minute because urgency is the only thing strong enough to cut through the noise.

None of this means you lack discipline.

It usually means your nervous system has been working very hard to protect you from overwhelm, criticism, or another experience of being told you are not enough.

Seen through this lens, procrastination is not a moral weakness.

It is a sign that something inside is already working very hard.

Two patterns that can look the same from the outside

From the outside, two people might both miss deadlines, delay starting, or sit frozen in front of a task.

They may even use the same words to describe it.

“I just cannot get going.”

But inside, very different processes can be unfolding.

For some, the block is driven primarily by fear.

For others, it is driven by overload.

And for many, especially those who are neurodivergent or who have grown up under chronic pressure, both patterns are present at once.

Understanding the difference matters.

What helps one pattern can intensify the other.

If the underlying issue is fear, more structure alone might not help because shame is still running the system.

If the underlying issue is overload, more self-talk or pressure can worsen paralysis because the brain is already carrying too much.

The goal is not to diagnose yourself through an article.

The goal is to recognise what is happening inside you, with more accuracy and less blame.

Many people recognise themselves in both patterns, and the balance can change depending on stress, context, and what the task means to you.

When procrastination is driven by fear

Judgement, not enough, uncertainty

If any of these feel familiar, it makes sense that starting feels loaded.

For many, starting a task can feel like a threat.

You might be afraid of being judged.

Of getting it wrong.

Of being seen as inadequate.

Of discovering that you really are not good enough.

This is the pattern we explored in Part 1, where procrastination acts as protection against shame, failure, or disappointment.

The nervous system reads the task not as neutral work, but as a potential emotional injury.

So it hesitates.

It delays.

It looks for escape or distraction.

Not because you do not care,

but because you care deeply about what the task might say about you.

Often the task is also tied to uncertainty.

You may not know how long it will take, what “good enough” looks like, or what reaction you will receive.

When the cost of being wrong feels high, delaying can feel like the only way to stay safe.

For other people, the struggle is less about judgement, and more about overload.

When starting is blocked by overload

Starting, switching, sensory load, too many steps

Here the block is not primarily about fear.

It is about the mechanics of beginning.

Tasks that seem simple to others can feel cognitively dense.

There are too many steps to hold in mind.

Too many transitions to manage.

Too many sensory or attentional demands arriving at once.

Initiation requires working memory, sequencing, prioritising, and the ability to shift from one state to another.

Some nervous systems, including those shaped by ADHD, autism, or sensory processing differences, can find these transitions genuinely taxing.

This can also show up when you are burnt out, sleep deprived, or carrying chronic stress, even if you do not identify as neurodivergent.

The brain is not refusing to work.

It is struggling to organise how to begin.

You might know what you need to do,

but your mind cannot locate the first step.

Or you start, and then get pulled away by an interruption, a notification, a sound, or a thought.

Coming back can feel like starting again from zero.

From the outside, this can look like avoidance.

Inside, it often feels like standing in front of a cluttered doorway,

knowing you need to pass through,

but not being able to see where to put your foot first.

When stress is high, both patterns tend to intensify, because the nervous system has less capacity to organise and begin.

Why stress makes starting harder

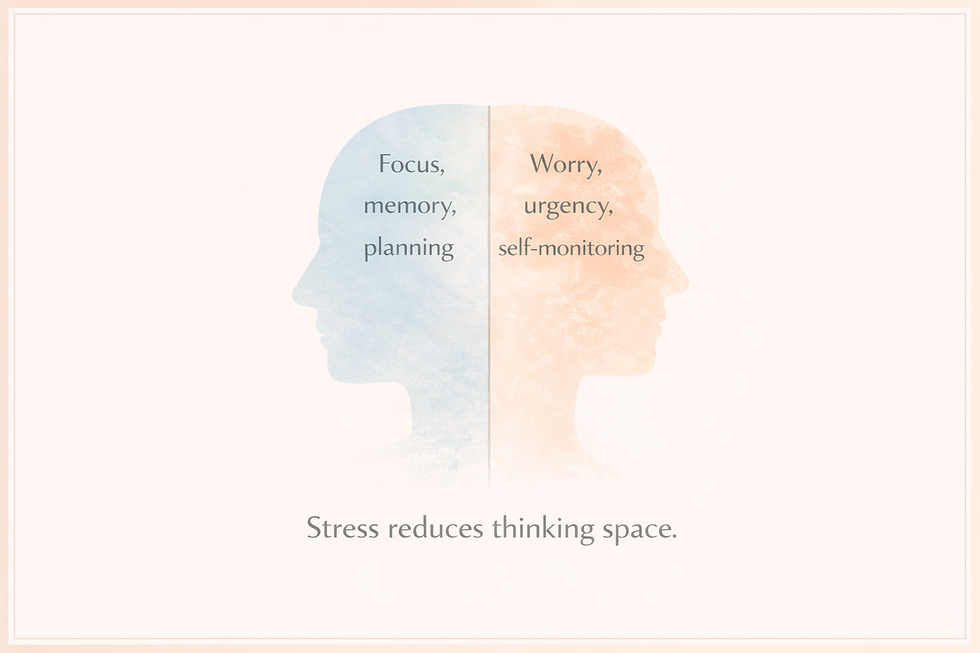

When stress is high, the nervous system shifts into protection.

Attention narrows.

The body prepares for threat.

This is helpful if you are in danger.

It is much less helpful when you are trying to write an email, begin a report, complete paperwork, or organise your life.

Stress increases cognitive load.

It adds an extra layer of internal noise.

Worry.

Urgency.

Self-monitoring.

For many people, starting becomes harder because the brain is trying to manage both the task and the emotional risk of the task at the same time.

You are not simply doing work.

You are managing pressure, self-evaluation, and the fear of consequences.

Under stress, the brain has less capacity for working memory, planning, and flexible thinking.

These are the very skills you need in order to begin.

This is why telling yourself to “just start” so often backfires.

If your system is already braced, the demand can feel like more threat.

The mind responds by tightening, freezing, drifting, or escaping into distraction.

For neurodivergent nervous systems, this effect is often amplified.

Sensory input can feel louder.

Distraction is harder to filter.

Transitions require more effort.

A task that might be manageable on a calm day can become unstartable on an overstimulated day.

So what looks like a small demand can tip the system into overload,

where shutting down becomes the only way to cope.

Seen this way, procrastination under stress is not a failure of will.

It is a sign that the nervous system is trying to keep you safe from something it experiences as too much.

Where the relational thread still matters

(especially for neurodivergent readers)

For many people, the difficulty with starting did not begin with adulthood.

It began in classrooms,

at kitchen tables,

and in workplaces where being different was met with correction rather than curiosity.

You may have been told you were careless.

Slow.

Disruptive.

Too sensitive.

Not living up to your potential.

You may have learned to mask.

To hide confusion.

To push through exhaustion.

To apologise for needing more time.

Over years, these experiences build a quiet story about who you are.

Someone who gets it wrong.

Someone who is behind.

Someone who is always being measured.

For neurodivergent people, this history can be especially painful.

When your brain works differently, you often encounter misunderstanding long before you encounter support.

You may have worked twice as hard for the same outcomes,

yet been treated as if effort did not count.

Even when you become high achieving,

the internal story can remain.

“I am one mistake away from being exposed.”

This is why “being judged” and “not good enough” can become intensified by lived history.

Tasks are not only difficult.

They are emotionally loaded.

They carry memories of shame.

Of rejection.

Of being told you are not enough.

Some people experience this as what is sometimes called rejection sensitivity.

A heightened alertness to disapproval.

A nervous system that is always watching for signs of being pushed away.

So when you avoid starting,

you are not only avoiding the task.

Some people use the phrase rejection sensitivity to describe this experience.

Not as a diagnosis, but as a way of naming how sharp disapproval can feel after years of being misunderstood.

You may be protecting yourself from an old, familiar hurt.

The nervous system remembers what it was like to be criticised, overlooked, or made to feel small.

It braces before it lets you try again.

This is why relational safety matters so much in this work.

Being seen with respect rather than judgement changes what feels possible.

Without safety, even the best strategies can feel like more ways to fail.

With safety, the nervous system can soften.

Effort becomes less loaded.

And starting becomes more possible.

What helps that is not “try harder”

If pressure has been your main strategy, it makes sense that your system is resisting, as we explored in Part 2.

When procrastination is driven by fear, overload, or a nervous system that is already stretched thin,

pushing harder rarely brings relief.

What helps is not more pressure,

but more support for how your brain and body actually work.

The aim of these adaptations is not to turn you into someone who never struggles.

It is to reduce the invisible friction that makes starting feel so costly.

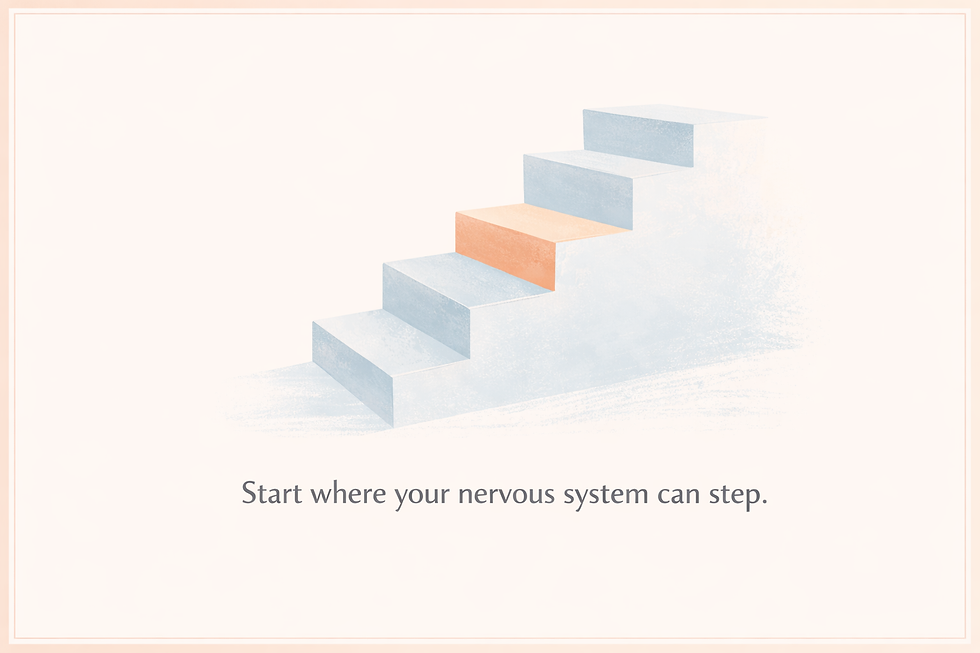

Think of this as building a kinder way back into action,

where your capacity is respected

and your nervous system is supported.

Below are ways of working with your nervous system rather than against it.

You do not need to do all of these.

Choose one that reduces pressure, and treat it as an experiment.

If starting feels hard, the answer is rarely more pressure. It is usually more support.

Reduce friction in the environment

Small changes in your surroundings can make a disproportionate difference.

When your brain is sensitive to distraction, clutter, noise, or visual chaos,

every extra stimulus takes up cognitive space.

This can make initiation feel heavier before you even begin.

A clear surface.

Fewer open tabs.

Softer lighting.

Less background noise.

These are not about creating a perfect setup.

They are about removing what quietly drains your attention

so your system has more capacity for the task itself.

Try this: One tab open, phone in another room.

Externalise the steps

(so your brain does not hold it all)

Many people get stuck not because they do not know what to do,

but because there is too much to hold in mind at once.

Writing out steps takes pressure off working memory.

It turns a vague demand into something you can approach.

You might begin with something as simple as

“open laptop”

“find the file”

“write the first heading.”

Let paper or a notes app hold the structure.

Your brain does not have to carry the whole staircase in one moment.

Try this: Open laptop, name the file, write one messy sentence.

Body first settling before cognitive effort

When the nervous system is braced,

thinking becomes harder.

Gentle physical settling can help you shift from threat

into enough steadiness to begin.

Slow breathing.

Stretching.

Standing up and feeling your feet on the floor.

A short walk before returning.

If your body is used to staying alert,

you might find it helpful to explore this more in

The goal is not to calm yourself perfectly.

It is to give your system enough safety to take one step.

Create micro-bridges for transitions and switching

For many people, the hardest part is not the work.

It is the transition into the work.

Starting requires a shift in state.

Switching requires another.

A micro-bridge is a small ritual that tells your brain,

“now we are moving.”

Setting a three-minute timer to organise your space.

Writing one sentence that names the task.

Opening the document and doing nothing else for thirty seconds.

These small bridges soften the shock of transition

and make coming back after interruptions easier.

Try this: Set a three-minute timer, and only open the document.

Use interest-based entry points, not demand-based entry points

Some nervous systems engage through curiosity, meaning, or momentum.

Demand can make them freeze.

So instead of starting where you “should,”

start where you can.

The easiest doorway.

The most interesting section.

The part you already have thoughts about.

Starting is not a test of discipline.

It is often a process of finding an entry point your nervous system can tolerate.

Compassionate accountability

(support without shame)

Many people do better when they are not alone with their tasks.

Having someone who knows what you are working on

and checks in with warmth rather than judgement

can provide structure without threat.

This might be a therapist.

A coach.

A colleague.

A trusted friend.

The key is that you are being accompanied,

not evaluated.

Recovery after avoidance

(repair rather than punishment)

Everyone avoids sometimes.

What matters most is what happens next.

Harsh self-talk deepens the cycle.

It increases shame.

It makes the next start even harder.

Gentle repair keeps the door open.

“Something got hard.”

“I stepped away.”

“I can come back in a smaller way.”

You are not meant to be perfect.

You are meant to keep coming back.

Therapy fit and linking

For many people, understanding procrastination through a nervous system and neurodivergent informed lens is deeply relieving.

It can also bring up grief.

Anger.

Sadness about how long you have been misunderstood,

by others

and by yourself.

This is where therapy becomes something more than problem solving.

In ADHD and neurodivergent informed therapy, the work is not only about managing tasks.

It is about building a formulation that makes sense of your history, your brain,

and the environments you have had to survive in.

It is about repairing shame.

Strengthening self-advocacy.

Learning how to pace yourself in a world that often demands more than is reasonable.

In therapy, we can look together at how fear-based patterns and executive functioning differences interact in your life.

We can explore how school, family, and work have shaped your relationship with effort and failure.

We can work on systems and supports that protect your energy rather than constantly draining it.

And we can build a steadier internal relationship with yourself,

so that starting becomes less tied to threat

and more tied to choice.

If you would like to explore this further,

you can find more in my ADHD therapy series here: ADHD Therapy: An Introductory Guide to Human-Centred Support

Closing

Procrastination is not a single thing.

For some it is fear.

For others it is overload.

For many, it is a complicated mix of both,

shaped by how their nervous system works

and how they have been treated along the way.

What matters most is that you do not have to face this alone or in shame.

With the right understanding and support,

it is possible to move from constant self-correction

toward a way of working that feels kinder, steadier,

and more aligned with who you actually are.

In Part 4, I bring Parts 1 to 3 together and share the psychological models, research, and clinical frameworks behind this series, so you can see where these ideas come from and explore them further.

Continue the series

Part 1: Why Procrastination Is Not Laziness

Part 2: Why Pressure Makes Starting Harder

Part 4: The Psychology Behind the Series (Models, Research, and References)

Related reading

FAQ

Is procrastination always anxiety?

No. For some people it is driven by fear, but for others it is driven by overload in attention, memory, or sensory processing.

What is executive functioning overload?

It is when your brain has too many steps, transitions, or inputs to organise at once, making starting feel impossible even when you care.

Can burnout cause difficulty starting tasks?

Yes. Chronic stress reduces working memory, attention, and energy, which makes initiation much harder even without ADHD.

Is difficulty starting a sign of ADHD or autism?

It can be, but it can also come from trauma, burnout, or long-term stress. This article focuses on how the nervous system functions, not labels.

Why does pressure make me freeze instead of act?

Because pressure activates threat in the nervous system, which reduces the brain’s capacity for planning and initiation.

Does structure help or make it worse?

It depends. Structure helps fear-based blocks but can overwhelm overloaded systems if it is too rigid or demanding.

Comments